53 year-old Superintendent Charles Teather was a home grown fireman have risen through the ranks since joining the brigade in 1911 when Superintendent William Alfred Frost was Chief Fire Officer.

He was born on 17th November 1884, at 136 Nottingham Street Rotherham, Yorkshire. His father Thomas Teather, aged 42, was a Gas Stoker, and was born in Wellow, Nottinghamshire, his mother Emma, aged 37, was born in Rotherham.

Charles had 3 older brothers, William, Thomas, and Henry, and an elder sister Emma. All were born in Rotherham. A later edition to the family was John who was born in 1887.

According to the 1901 Census the family had moved to 7 Fleet Street, Blackpool, Lancashire, and Charles now aged 16, was working as an errand boy at a paint/china shop.

10 years later, in 1911, Charles, had moved again and was now living at Flat 6, Rockingham Street Fire, Sheffield, Yorkshire with 4 other young Sheffield Fire Brigade Police Firemen.

On 27th December 1915, Charles married 30 year-old Sophia Taylor from Clayworth, Nottinghamshire at Clayworth Parish Church.

On 15th August 1917, Charles and Sophia's son Cedric Nigel was born.

On 26th May 1920, Charles and Sophia's daughter Iris Mary was born.

In 1925 Police Fireman Charles Teather was pictured with other members of the brigade at Rockingham Street Fire Station

In 1929 Charles was promoted to Police Sergeant/Fire Officer.

For his gallant conduct at a fire at Darnall in 1932 when four children lost their lives, he was awarded the silver medal of the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire.

In 1934 Charles was promoted he was appointed 2nd Officer.

In 1936 he received the medal of the National Canine Society for rescuing a dog from a fire.

In 1936 he was appointed Chief Inspector, and 1937 On the departure of Superintendent Breaks CFO, He was appointed to Acting Superintendent CFO.

In 1938 Acting Superintendent Teather was formally appointed Superintendent, and Chief Fire Officer, Sheffield Fire Brigade.

Unfortunately, in October 1937, his wife Sophia passed way at the age of 52.

In 1939, 55 year-old, Charles and his 22 year-old son Cedric Nigel, an Insurance Clerk, were living at 1 Fire Station Flats, Division Street.

Because of the housing development that had taken place a single pump Station had been opened on the Manor Estate with the Firemen living in the adjoining Corporation houses, and one fire engine and crew were stationed at the Divisional Police Station at Whitworth Lane, Attercliffe, to provide the first attendance to the fire risks in the steelworks in this area.

The Firemen were now working a two-shift system consisting of eleven hours of day duty, and thirteen hours of night duty with one day off per week.

Preparation for War

|

Owing to the possibility of a war with Germany, and as a result of the Civil Defense Act 1937, which enabled local authorities to raise an Auxiliary Fire Service the AFS came into being. The new volunteers attended weekly training classes with regular Firemen as instructors. and the training and equipping of AFS began to advance rapidly. 1 Inspector, and 5 Police Firemen were transferred the AFS to deal with the delivery of machines and appliances, and to undertake training. By 10th August 1939 1,200 Auxiliaries had been trained. |

|

The anticipation of war finally became a reality when Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, read out the Declaration of War with Germany at 11.15am on September 3, 1939, 15 minutes after it was delivered by the British Ambassador in Berlin to the German Government. On the outbreak of war in 1939 the Auxiliary Fire Service was embodied in the City's ARP structure, and AFS volunteers were posted to the 20 newly created temporary Fire Stations. In 1939 the rank structure of the AFS mirrored that of Sheffield Police. i.e. Inspector and Sergeant. The notable AFS additions being the titles of Fireman and Firewoman. We have been able to recover the records of 1,072 of the 1,200 AFS personnel listed above by researching the 1939 England and Wales Register. Registered AFS Personnel 1939 (Opens on a new page) |

Sheffield Fire Brigade - Wholetime Personnel 1st January 1940 (4 Officers and 65 men)

View the full list of Sheffield Firemen and their families (Opens on a new page)

The 1925 and 1940 Establishment Documents were provided by the late Ronald Weston SYCFS ACO retired. In the following paragraph he details how he came by the record:

"There was a moment in the Sheffield Brigade when someone near the top

decided to get rid of old documents, namely ‘Nominal Rolls’ of the SFB period

during WW2. These were the old style ‘bound documents’ in ledgers with pen

and ink entries from the clerk of the period. The instruction was to tear out the

pages and destroy them in the coke-fired boiler. It could well be that they were

surplus to need, but my colleagues had the feeling that it was a clear out.

Consequently they removed the six sheets which related 1940 and 1941, and

passed them to me for safe keeping!. I kept these for interest, partly because my

father was on the lists as well as many I knew from knowing them then and also

later when I joined the service in October 1948.

Ronald Weston 2014"

Sheffield City Fire Brigade Establishment 1940

View the 1940 Sheffield Fire Brigade Establishment (Opens on a new page).

| View the original rescued pages for 1940 |

Appliances 1940

| Apparatus: | |

| No. | Type |

| 1 | 700-900 gallons per minute Motor Pump |

| 1 | 600-750 gallons per minute Motor Pump |

| 2 | 300-500 gallons per minute Motor Pumps |

| 2 | 300-350 gallons per minute motor pumps |

| 1 | 300-350 gallons per minute Trailer Pump |

| 1 | 80-130 gallons per minute Trailer Pump |

| 1 | 90 foot Motor Turntable Escape |

| 1 | Rescue Tender |

| 1 | 18 h.p. Tender |

| 1 | 14 h.p. Tender |

| 1 | General Service Wagon |

| 2 | 40 gallon Foam Trailers |

| 2 | 600 gallons per minute Air Foam Branch Pipes |

| 1 | 48 foot Fire Escape, etc |

Headquarters: Division Street – Telephone Number 22222

Supplementary Station: Attercliffe (Howden Road) – Telephone 41117

|

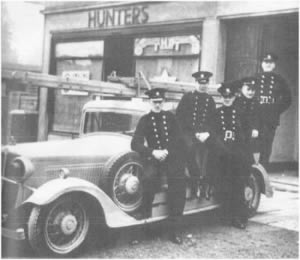

Photograph Courtesy of Sheffield Star This was typical of many of the AFS Units at the time. |

Sheffield Police Fire Brigade and the Auxiliary Fire Service. Whilst both were expected to rise to the challenge of potential of German bombing, their uniforms where entirely different.

|

|

As shown in newsreel Footage of the time the Sheffield Police Firemen wore the leather fire coat introduced in the 1930's, and the traditional brass helmet. This apparel was dispensed with on the advent of the National Fire Service (NFS) in 1941. |  |

AFS Firemen wore the traditional woolen fire coat and the magnesium steel helmet. This uniform was the one adopted by the NFS in 1941, and remained in service until 1948. |

| Sheffield City Fire Boat 'Alpha |

In 1939 the refurbishment and fitting out of an ex-ship's lifeboat to create a fireboat to protect Sheffield Canal Basin, and the factories bordering the canal, was commenced.

In true Sheffield Fire Brigade fashion, the skills of its firemen were utilised to undertake the work.

|

The Fireman on the right is Laurence 'Lol' Walker in the leather coat, who being a qualified joiner was the lead converter. Whilst his assistant on the left is Eric Searston who became later CFO in the East Riding Fire Brigade. They are sitting on the roof of Alpha during its conversion. Lol Walker moved to the East Riding Fire Brigade as a Sub Officer in 1955 and retired in 1969 as an ADO. |

Training of the AFS continued at a pace by the Sheffield Police Fire Brigade, and in the city centre many of the buildings had been sand bagged and the windows covered with sticky brown paper to prevent the glass shattering when bombs fell. Posters warning amongst other things that "walls have ears" and "careless talk costs lives" appeared in prominent places.

Training of the AFS continued at a pace by the Sheffield Police Fire Brigade, and in the city centre many of the buildings had been sand bagged and the windows covered with sticky brown paper to prevent the glass shattering when bombs fell. Posters warning amongst other things that "walls have ears" and "careless talk costs lives" appeared in prominent places.

Sporadic visits to the district by German bombers which began in August and September were recognized as reconnaissance expeditions, and after the treatment metered out to Coventry and Birmingham, the authorities, and most of the public-knew that Sheffield was scheduled for a mass raid. It came on the night of 12 December 1940 when the Luftwaffe launched operation 'Crucible' which according to the Imperial War Graves Commission, would result in 562 people losing their lives on the nights of 12th to the 16th inclusive.

In conjunction with increase in the Fire Service strength, precautions against air raids were in hand before the declaration of war with Germany had been made. Anderson shelters, made out of corrugated steel had been delivered to many householders.

It was then up to the householder to dig a hole large enough to accommodate the shelter. This was done with the help of relatives, friends and neighbours all helping each other to slot and bolt together the metal sheets that made the shelters. The shelters, being built below ground were then often covered or surrounded with the excavated material.

Larger shelters were built in school grounds. Teachers and older pupils were given duties of guarding these shelters. The shelters were later to become the classrooms at times when the air raids became more prevalent. Barrage balloons began appearing in the skies, their purpose was to entangle any low flying enemy aircraft.

Fire Service Wholetime Resources 1940 (opens on a new page)

| The Sheffield Blitz |

As previously stated, the attack on Sheffield was code-named Crucible by the Germans, a reference to the pioneering steel making technique developed in Sheffield in the eighteenth century. From several airfields in occupied France, the Dritte Luftflotte sent out some 300 aeroplanes, mainly Junkers JU-88s, Dornier 17s and Heinkel 111s. On the 12th the alert was sounded at 7 p.m. and within a few minutes German planes were over the city and facing a heavy barrage. Flares were followed by showers of incendiaries. An aerial bombardment that was to last for approximately nine hours had started. The "all-clear" went at 4.17 a.m., by which time scores of fires were burning, throwing ominous glares over great areas. in the city.

Dornier Bombers |

It is estimated that approximately 450 H.E. bombs, in addition to six parachute mines and many thousands of incendiaries, were dropped during the raid of December 12th-13th. Enormous damage was done, particularly in the centre of the city and in the north-west and south-east. Casualties, while heavy, were lighter than was feared when reports disclosed the extent of the damage. |

The evening of Thursday, which is early closing day in the city, has always been a popular night for down-town entertainments. This particular evening was no exception. Places of entertainment were crowded, a dance was in progress in the Cutlers' Hall, hotels and restaurants were busy.

In view of the presence of so many people in the city it was little short of a miracle that the number of dead did not number well over a thousand. Fortunately there was no direct hit on the auditorium of any theatre or picture house. These were cleared after a time on police orders, and though the Central Picture House was destroyed by fire, and had more than 400 persons in it when the blaze started, they were all got safely away to shelters.

The Wholetime Police Fire Brigade crews from Division Street reinforced by the part-time men from Sheffield's AFS Stations were quickly in the City Centre and were attending the fires caused by the first wave of marker incendiaries when the second wave of bombers arrived.

| What happened next is best told by the Firemen who were there. |

| Fireman Christopher Eyre - His Story Abridged from an original article by Len Doherty - Courtesy of Sheffield Star |

IF a man who went through it all tells you he wasn't afraid that night you can take it he's lying. "At first it wasn't so bad, though bad enough. We were turned out right at the start to save the Empire, and fought the fire there for an hour.

" Then the bombs started falling all along The Moor." " It's almost impossible to describe. We could hear the whistling and the crashes, we were ringed in by flame, and yet I seemed to be in a vacuum.

"You had to concentrate with all you'd got on the job and ignore what was happening within yards of you."

Even the "regulars" had never fought these conditions before. But there were only 60 of them and the 1,800 strong firefighting force was mainly made up of shopkeepers, businessmen and workers in "reserved occupations" whose experience had been confined to backyard bonfires before the war.

|

| The 'Morning After' Photograph taken from outside the Empire Theatre, looking along Charles St, and across Pinstone Street. From Sheffield Star and Telegraph archives |

"I remember looking down The Moor once and seeing the whole place alight from end to end with buildings collapsing into the street. Now and again we dived under the appliance as a big one whistled down beside us, and once I was blown on my back without receiving a scratch." The team was directing its hoses on to the furiously blazing Campbell's furniture store. Without let-up the waves of bombers were pouring down their loads. From one end to the other the firemen on The Moor were straddled by bomb-bursts.

"While we were fighting the fires in Pinstone Street," Mr. Eyre goes on, one of our chaps came to tell me that one appliance which had gone to Porter Street had been blown to bits (See notes). Two men went with it, both my close friends."

"Later in the night we were fighting a tremendous fire at Bramall Lane, but lack of water sometimes. made it impossible to do anything”

"We were using anything on wheels to draw the pumps, driving over the debris where it was possible- and with hardly any idea of what streets were blocked or open."

High Street from Change Alley. AFS Trailer Pump in the centre background. From Sheffield Star and Telegraph archives |

AFS Fireman Bill Wright - His Story I was driver and pump operator on the first machine. On reaching the top of Normanton Hill, Jerry saw our headlights and started diving and firing tracer bullets at our machines. We managed to get through to the bottom of Granville Road, where we met an amazing sight. Tramcars and overhead wires were all over the road. We carried on to Fitzalan Square, where the Marples public house had just received a direct hit. We placed three machines on the Moor and one down Porter Street. |

At 12:42 am on the 13th December Sheffield Police Fire Brigade requested assistance from neighbouring Fire Brigades, and in response to their request Manchester and Nottingham sent ten pumps each, Bradford sent six, Barnsley four, Doncaster, Wakefield, Halifax, and Huddersfield sent three each, and Rotherham, Wombwell, Leeds and York all sent two. Manned pumps also arrived from Mexborough, Wortley, Hoyland, Kiveton Park, Thorne, Wath, Cudworth, Pudsey, Morley, Spenborough, Pontefract, Shipley, Bingley, Keighley, Brighouse, Elland, Holmfirth, Castleford, Mirfield and Ossett. The outside help totaled 70 pumps and 522 men. Some of outside pumps had difficulty getting into the city and had to be guided round bomb craters by men of Sheffield Transport Department. They and the local services were hampered by water freezing under their feet and on their clothes.

|

A Fireman stands helpless in the midst of chaos From the book - Sheffield at War - by Sheffield Star and Telegraph |

AFS Fireman Jack Gee - His Story:

AFS Fireman Jack Gee - His Story:

On the Thursday night blitz, Jack Gee was on duty at Archer Road Fire Station and was turned out with his crew to the City Centre.

He lived in the region of St. Mary’s Road and whilst driving down London Road he could see that all that area had been flattened by bombs and he feared for his wife and child but could do nothing.

He attended fires at the Moorhead and a bomb dropped close by killing some of the crew of the engine and injuring others. Jack Gee was also badly injured in the arm and was taken to a shelter near Moorhead until he could be taken to hospital. What follows is in his own words:

On Thursday, 12th December, 1940. I was on duty at Archer Road Fire Station and we were turned out to the City centre. At that time I was living in the neighbourhood around St. Mary's Church at the bottom of The Moor. As we drove down London Road, I could see that all that area had been flattened by bombs. I couldn't help worrying about my wife and wondering whether she was safe. But there was nothing I could do about it.

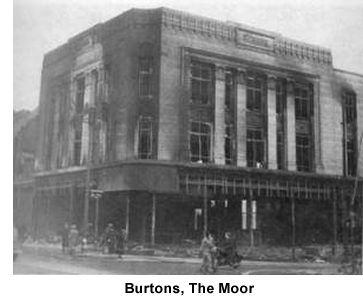

We were fighting fires at Moorhead when our machine took a direct hit. Those of the crew who were not killed outright were badly injured. As I lay on the pavement trying to recover my senses, I realised that my left arm was in a terrible state. Eventually someone pulled me away to the shelter of the doorway of the Empire Theatre. Then I was taken down to an air raid shelter. I was there about three hours and the people in the shelter covered me up. I was suffering from shock and cold. A woman actually sent her fur coat down to cover me up but I sent it back. After two or three hours, some people enquired if any injured firemen were there. It was the ambulance men and they put me on a stretcher in a loading bay. In actual fact we came through he loading bay of Burtons the Tailors to get onto the road itself, which was Porter Street. Then one man came back and told us to hang on a minute as the Germans were machine gunning.

We were fighting fires at Moorhead when our machine took a direct hit. Those of the crew who were not killed outright were badly injured. As I lay on the pavement trying to recover my senses, I realised that my left arm was in a terrible state. Eventually someone pulled me away to the shelter of the doorway of the Empire Theatre. Then I was taken down to an air raid shelter. I was there about three hours and the people in the shelter covered me up. I was suffering from shock and cold. A woman actually sent her fur coat down to cover me up but I sent it back. After two or three hours, some people enquired if any injured firemen were there. It was the ambulance men and they put me on a stretcher in a loading bay. In actual fact we came through he loading bay of Burtons the Tailors to get onto the road itself, which was Porter Street. Then one man came back and told us to hang on a minute as the Germans were machine gunning.

We stayed in the loading bay for a few minutes and we could hear machine gun bullets hitting the brickwork. By this time we could not hear any of our anti-aircraft guns firing from the gun sites around the city. They had probably run out of ammunition. They were all silent after about two o'clock and the planes were coming over unmolested.

We stayed in the loading bay for a few minutes and we could hear machine gun bullets hitting the brickwork. By this time we could not hear any of our anti-aircraft guns firing from the gun sites around the city. They had probably run out of ammunition. They were all silent after about two o'clock and the planes were coming over unmolested.

They finally got me into an ambulance which was parked on The Moor. There was a girl in the ambulance of about eighteen years old. She was with the ambulance crew and sat in the ambulance all the time. We went down The Moor and practically the whole of The Moor was ablaze. We twisted and turned and I found out that the driver had to detour and go up so many streets to try and get down The Moor. Eventually we went up Ecclesall Road to get to the Royal Hospital (situated on Devonshire Street and now demolished). The girl sat there all the time. She was as cool as anything and never budged.

When we arrived at the Royal Hospital, we entered at the back entrance in Eldon Street. All the windows were out and the nurses were moving about with hand torches. They were trying to find out where everybody was. They told the ambulance men to take me on to Jessops Hospital but the ambulance men told them that there was no chance of getting up there. While they were arguing, I heard a voice saying, 'I know who you are, but where are you from?' I realised that they were talking to Bill Jones, another crew member, who had been picked up at the top of The Moor and had arrived just before me. So I put them right as to where he was from.

At about 4 o'clock in the morning, they were able to put the lights on in the hospital. I looked around me and saw that there were rows and rows of beds and stretchers toe to toe, all jam packed together. They were taking the most serious cases first.

These were put on a table and given a general anesthetic, using ether. After my operation I came to in a bed with my left arm stuck out like a birdcage.

These were put on a table and given a general anesthetic, using ether. After my operation I came to in a bed with my left arm stuck out like a birdcage.

The next day Bill and I expected people to come from the station, but no-one came. We finished up in a ward with four other firemen but we were unable to find anything out from anyone. Eventually, some scouts came round the ward to ask if any patients wanted errands done. They said they would do them. By this time, two days had gone by since the night of the bombing and remembering the damage in the St. Mary's Road area where I lived, I was worried about my wife. So I got one of the scouts to go down there and see if he could find out anything about what had happened. When he came back, it was not good news. He said that my house had been bombed and there was nobody there. The whole area was more or less devastated. That was a very worrying time for me.

On Saturday night around 9 o'clock, the nurse came in and said, 'Mr. Gee, we've got a surprise for you. Here is your wife!'

My wife had been trying to find me, and I had been trying to find her. The whole of our house had been destroyed, and there was hardly anything left. Since then, my wife had been running round the fire stations trying to find out what had happened to me.

We got another air raid on the Sunday night. We were still in the Royal Hospital and we thought the bombs were landing close by. It did sound like it. We had a gunner in with us from the Norton Gun Site with damage to his ears. He told us that they were not bombs but guns and not very far away. We laughed at him over this but we found out from the vicar of Fulwood that there was a gun sited outside the hospital. It turned out a convoy of forty guns had been shipped into Sheffield that very day, so they must have known that another raid was coming. Guns were put on street intersections. There was another one outside the Somme Barracks on Glossop Road.

The Sheffield raid on the Thursday night was the longest single raid of the war. Coventry and one or two other places were more concentrated but did not last as long. The Sheffield raid last from 7 o'clock in the evening until 4 'clock the next morning, and for the last four hours we had no defences. There was a story that a lorry and trailer were seen fully loaded with shells on East Bank Road, looking for the Norton Gun Site. I don't know if they ever got there. The raid on Sunday, 15th December wasn't as long. I think the Germans got a shock when all those guns opened up. It must have deterred them somewhat.

A week later, the cases that the doctors thought were going to be a long while recovering, were moved from the city hospitals. Obviously, the authorities were expecting more raids. I was taken to Wakefield to a hospital which had previously been a mental hospital. At the beginning of the war, the mental patients had been transferred to other institutions and then this one had been opened up as a military hospital.

At this time there were more civilians injured than military so they began to admit civilians as well. I was up there three or four months. After Bill Jones had been in hospital two days he got gangrene and they had to take his leg off. Doctor Forbes, the Police Surgeon, examined us and he decided whether or not we would be fit to return to service. After eight weeks, Bill Jones was given his discharge. If there was any doubt, it was possible to have a thirteen week period before the doctor made a final decision. I got a letter sent to my house after thirteen weeks giving me my discharge.”

W. H. Livsey - Ambulance Driver - His story:

Thursday 12th December 1940 to Friday 13th December 1940

5:00 pm

Afternoon- V. Brammer & Girlfriend, Phyl and I went for run to Bakewell. We had tea at the George Hotel, Hathersage. The waitress speaking of the recent bombings said that the Germans would not find Sheffield. It was the best Blackout City in England. So an airman friend of hers had told her.

6:30 pm

The was a slight mist when I arrived home at Uplands, which is at the side of Sugworth Hall, off Sugworth Road, Bradfield, Sheffield. I went in for a warm before getting the new car out and going into work for the 10 pm to 7 am shift.

7:05 pm

I started the car up, and Joan on hearing this said it was sounded like an aeroplane. I laughed but then heard an explosion in Sheffield, so I decided to wait at home for a bit. From the field at the back I could see huge fires which I thought were over the East End works. Brilliant flares were dropping and floating slowly to earth. Our anti-aircraft batteries were trying to shoot these out. Tracer bullets could be seen, and the enemy were evidently trying to shoot down the barrage balloons. The noise was terrific. The gun nearest our house changed its firing direction and fired out over our house to meet the incoming planes. There wasn't a minute that passed without the crash of bombs over Sheffield.

About midnight there was a slight lull in the bombing, so I suggested setting off with the car, but the attack started again. I waited whilst 1:25 am and then decided that the huge fires to be seen were not over Crosspool, so we should travel that far and investigate.

Passing Moscar Top saw two cars smashed up. When I had just passed Blackbrook, shells were bursting above us so I pulled up and sat under wall until guns changed their trajectory. Seeing as it was quiet for a moment I made a dash for Crosspool leaving V. Brammer at Coldwell Lane. Watching for shell bursts near the Sportsman Inn, I failed to notice debris in the road, the result of a landmine in Cardoness Road and I nearly turned the car over.

I arrived at Watt Lane. Phyl's Mother and Father were next door at the Bradshaw's. I told them of the damage in Manchester Road and Benty Lane. I borrowed Phyl's tin hat and set off for town. The police stopped me at Kings Head, as I was running without lights. I saw a huge explosion down at Broomhill, and I got the wind up and went to Lydgate Lane Ambulance Station. All their ambulances out of service through crashes and burst tyres due to glass.

There was no chance of a lift to town, so I decided to try again. I got as far as Oak Park when I saw soldiers rushing out of Tapton House Road. I pulled into the side of the road, opened the car door, and was about to get out when a bomb, exploding at the back of Redlands, the explosion lifted my car on to its side and threw me out on to the causeway. I was only shaken and five soldiers helped me put the car back on four wheels again, and luckily it still ran. The front wheels were a little damaged and petrol had spilled out of the tank but it was still serviceable.

Next I went as far as the York Hotel at Broomhill. The house next door but one to Col. Lycett's, was on fire. I next turned down Glossop Road, and saw St Mark's Church was on fire.

A bomb had dropped on my right down Newbould Lane, and about at Wilkinson Street I saw a huge fire in front of me (Reuben Thompson's Garage), so I turned left and went up to the University and turned to go down Brook Hill. A crater the width of the road stopped me, so I backed up and went down Leavygreave Road where I had to bump over fire hoses. There was a small fire at Jessop’s Hospital, and I turned down Gell Street into West Street and travelled as far as Regent Street, where the Boots chemist shop had received a hit. Toilet rolls were all over the place having been blown out of the window. I turned up Regent Street (as West Street was littered with broken glass,) and across Broad Lane into Red Lane. on passing St. Vincent’s church a stained glass window was blown out in front of me. I came out near the bus sheds, and they were backlit with fire. Church Street, Campo Lane and St. James Row were a mass of flames. I got as far as Scotland Street and became entangled in tram wires, the car engine stopped, and as I got out to restart it the new Police Station received a direct hit and instantly became a mass of flames. I just got the car into reverse to back round to Scotland Street when Shaw’s newsagents blew up twenty yards in front of me. The blast blew me back to Solly Street. I got up Scotland Street and turned down Lambert Street when three explosions blew out the windows of the flats, some debris dropped on the back of the car but did not stop me.

I came out into Gibraltar Street, and I was stopped by a convoy of fire tenders from Huddersfield and Dewsbury. They were stopped by a huge pile of three tramcars piled in a heap. A bomb had dropped on top of them. The officer-in-charge wanted to know how to get to the Central Fire Station. I directed them and noticed a big black Rolls Royce car and trailer, which I afterwards saw in St. Mary's Road all smashed up.

Crossing the road I went across Spring Street and arrived at the Central Ambulance Station. I parked "Thunderbolt" under the shed and went into the Shelter under Mellows where the Staff were. As I went down the steps a fire bomb landed on the roof of Mellows and started a big fire. After reporting to Capt. Kenny I went upstairs again and found the whole of the building above a mass of flames.

Crossing the road I went across Spring Street and arrived at the Central Ambulance Station. I parked "Thunderbolt" under the shed and went into the Shelter under Mellows where the Staff were. As I went down the steps a fire bomb landed on the roof of Mellows and started a big fire. After reporting to Capt. Kenny I went upstairs again and found the whole of the building above a mass of flames.

I went back and told Capt. Kenny who said they would be alright, but he evidently changed his mind and ordered everybody out I started the Daimler and ran it down the road full of spare tyres, A number of ambulances in the garage not in service were driven out and parked away from the fire which was showing signs of spreading across the road.

The heat was unbearable. I turned on the hosepipe and sprayed the petrol pump and my own car and pushed it as far from the flames as possible. The Fire Brigade arrived but could not get water so went away. I was sent to Oxford Street Chapel with two ARP Girls as attendants on ambulance 340.

I arrived to find it had received a direct hit and that a number or people were buried in the houses below. An old man, who said his family were under the first house, told me they had pleaded with him to stay with them in the cellar, but he would not and so lived to tell the tale. As there was no chance of getting at them for sometime I went hack to Corporation Street.

In Spring Street I met Capt. Kenny who sent me to Shoreham Street tram sheds for a number of cases. I got three of them alive, one of the fire attendants told me she lived next to the Cathedral in the Church House and that all her people were there, so I decided to run round and see what had happened at Church Street and St. James Row. They were burning fiercely. The nearest we could get was Leopold Street so the ambulance was parked and I asked a fireman if it was safe to go. He said no, but after explaining, he said he would help us but that we went at our own risk. This made me laugh. It seemed strange somehow in the middle of an air raid.

We found the house shattered but only one old man was injured so he was taken with the rest to the Royal Hospital. These two jobs, although not far from the station, took three times as long to reach as it was impossible to travel along nine out of every ten roads. After unloading my patients I saw Harry Beck (another driver) behind the Hospital door sobbing. Thinking it was an attack of nerves I took no notice of him, but on entering the Lodge I learned he had just been told his brother George (another driver) and Percy Wood his attendant had been killed. Attendant Dolphin who had been with Harry came with me and as we set off for Carwood Avenue the “All Clear" went. The raid had been in progress for ten hours.

On arrival we found that the casualties were all people in the air raid shelters. Out of about fifteen Anderson Shelters, all built without blast walls and containing three or four people each, only two were alive. These we taken to Fulwood Annex, the Royal being full.

On returning to the Station we were sent to Reginald Street where the rescue parties had recovered some bodies - two alive and one dead. They were taken to the Royal Hospital. Taking the bodies to the mortuary we found that out of fifty three bodies only seven had been identified. The bodies of some A.F.S. firemen were in canvas bags, not much bigger than sand bags, they could not be recognised as men.

As it was now about 12:15 pm, I packed up and went home.

| "Fire Fighting Heroes of the Blitz" |

An article by the "Star" reporters T.H. Cramb published on the 9th October 1944 has been included as it gave an excellent description of the events of the nights of the 12th and 13th December 1940

There are several details of the Sheffield blitz, December 1940 which have never come to light. Some never will, but one service which had many heroes during the rain of fire and destruction on the city was the Fire Service.

Some of the work which the Auxiliary Fire Service - as it was then known - performed that night can now be told.

- Heroism, devotion to duty, service under difficulties, undaunted spirits, and hard work all rolled into one aptly describes those firemen’s night way back in 1940.

- They were called and not found wanting. They answered the call of the sirens, they stood their ground, and they did their best.

- Appliances got stuck in bomb craters. In some cases the crews managed to get them out; others had to be left as they were damaged.

- One pump received a direct hit as it was working and three of the crew were killed and another injured, while another pump was wrecked by the blast of a nearby bomb.

- During the night five members of the Service were killed and 56 injured, 12 of them seriously - a very small number considering the total number of personnel actively engaged during the raid.

- Information had been received earlier in the evening that Sheffield was likely to receive a strong visit from the Luftwaffe that night, with the result that as much preparedness as possible was made.

- Machines, equipment and men stood at the ready -

THOSE PERSONNEL CONSISTED OF APPROXIMATELY 1,200 FULL-TIME MEMBERS OF THE A.F.S. AND PRE-WAR FIREMEN, AND THEY HAD OVER 200 APPLIANCES.

When the alert sounded between 900 and 1,000 volunteer or part-time members of the A.F.S. answered the call, and reported to the 27 stations in operation.

Call for Help

Within a very short time all were engaged on fires raised by the enemy in all parts of the city, and a district call was sent out for additional help.

That help first came from Rotherham, Barnsley, Doncaster, Mexborough, Wortley, Kiveton Park, Cudworth, Thorne, Wath, Hoyland and Wombwell, but as the raid developed a regional call brought assistance from Chesterfield, Leeds, Bradford, Wakefield, Manchester, Nottingham, Lincoln, Sleaford, Birmingham and Grantham.

Owing to the system then in force, all the outside brigades had to report to the Headquarters in Division Street, Sheffield, and it speaks well for the authorities when it is said that all reported safely, and were immediately dispatched to fire zones without loss, or incident.

The first calls were to Hounsfield Road and to the Neepsend district.

Within a short space, however, no fewer than 550 calls were received by telephone at the control room in Division Street.

Many other information's were sent by messenger, with the result that as fast as reinforcements arrived there was a task waiting for them.

Much of the smartness of the outside brigades in arriving at their allotted fire zones was due to about 20 members of the Sheffield Transport Department.

Tram drivers, bus drivers, and conductors unable to do anything with their own vehicles, offered themselves as guides to outside brigades and directed them to the incidents. Those few can be classed among the unsung heroes of the night.

Thousands of fires were breaking out in various parts of the city, and many an engine and pump crew dealt with several outbreaks other than the one they were sent to.

Half an hour after sounding the alert the A.F.S. met their first big set-back. Water ceased to be obtainable from the mains, and quick thinking had to be done to keep most of the machines supplied.

Water from Don

Public baths and the few emergency tanks in being were tapped and the water relayed. Water was also relayed some distance from the river Don.

Many fires were kept in check by water which had accumulated in bomb craters adjoining burst mains, and many lines were kept operating by the fire float on the canal.

It is estimated that well over 36 miles of hose were in use that night, in addition to several miles attached and operated by industrial fire brigades.

Those industrial brigades pulled their weight, and gave useful assistance in all sorts of ways to the A.F.S.

One remarkable feature of the whole night was the fact that the telephone system of the fire brigade continued working throughout the whole raid, this despite the fact that two stations received hits, these being Sharrow Vale and Hoyle Street.

Brave Canadian

What few civilians were about in the streets in the thick of the raid gave useful assistance to the pump crews in helping to run out hose and in many other ways.

Tribute must be paid to the Canadian soldier who perched himself on the dome of the Empire Theatre and played a hose on the raging fire at Campbell’s furniture store - which, incidentally, was the first real big fire of the raid.

ANOTHER PROBLEM OFFICIALS HAD TO FACE WAS THE SUPPLYING OF PETROL TO KEEP THE PUMPS AND APPLIANCES GOING, BUT THIS WAS OVERCOME BY THE LOAN OF A CORPORATION PETROL TANKER WHICH, DRIVEN BY CORPORATION EMPLOYEES, VISITED ALL PARTS OF THE CITY AND FILLED UP THE APPLIANCES.

Hundreds of fires were reported by people who had seen reflections of other fires in house and shop windows, and calls were also received for fire engines to stand by at business premises “just in case.”

Nurse Fought Fire

Nether Edge Hospital received a bad hit, and fire was raging in on quarter - yet the firemen found a small nurse tackling it on her own with a bucket of water and a stirrup pump.

Two small boys, acting as volunteer messengers in one part of the city, put out numerous incendiaries, and then curled themselves up by a pump and went fast asleep - tired out and oblivious of bombs dropping in the vicinity.

Food Problem

One woman, with sandbags under her arms, followed the firemen into one building and dropped her sand on every little outbreak she passed and then went outside for more sandbags.

She would not listen to orders to get to safety.

The following morning another problem faced the authorities - food for the crews. Certain arrangements had been made but these were planned around the city receiving the all-clear.

Anyway, one station was immediately turned into an eating house, volunteers arrived and in a very quick time all had a hot breakfast.

In addition, several large houses - businesses and private - devoted all their time to supplying food to the A.F.S., while the YWCA in Division Street immediately opened the premises as sleeping quarters, crews falling asleep in their soaked and mud spattered clothes.

What few women had then joined the A.F.S. stuck to their tasks throughout the night, and refused to be relieved when the raid was really heavy.

Civilians Helped

A feature of the two raids, as seen by A.F.S. officers and men, was that whereas on the first night civilians were under cover as much as possible, they were out and about on the Sunday night, ready to give the brigade any assistance they could.

As one officer put the position the first night: “When the all-clear sounded the earth seemed to belch forth thousands of people, just like ants coming from underground.

“They were silent and the only noise was the roaring of the flames and the crunching of the broken glass under the peoples feet.

“It was uncanny; those silent thousands emerged from apparently nowhere.”

The Sunday was the opposite. Those same people came out and offered to brave all the dangers in their anxiety to lend a hand."

| Water Supplies |

As water supplies ran low, water from Glossop Road, Park and Sutherland Road baths was used for fire fighting. Water was also taken from local rivers and from the canal basin.

Owing to the fracturing of water mains in the centre of the city, fires got completely out of control for a time. Several large buildings not directly affected by the raid were involved, and in some cases completely destroyed by fires.

Happily a change in the direction of the strong wind helped the fire-fighters, and all the outbreaks were under control soon after daylight.

| That night 8 Firemen died, 1 Fireman was fatally injured and 40 others were injured. |

| Name | Age | Location |

| Norman Elliott | 35 | Sheffield Water Department Turncock Sheffield Police Fire Brigade (Attached from Sheffield Water Department to work with Fire Brigade.) 35 years of age. Died on 12th December 1940, at Union Street. |

| Alfred Garlick | 30 | Fireman; Auxiliary Fire Service, injured 12th December 1940 at Archer Road, died December 14th 1940, at Royal Hospital. |

| Arthur Moore | 28 | Fireman/Driver Auxiliary Fire Service, died on 12th December 1940 at Burgess Street. |

.jpg) Frederick Parkes-Spencer Frederick Parkes-Spencer Photograph courtesy of: Joanna Allanson |

36 | Fireman; Sheffield Police Fire Brigade, died on 12th December 1940 at Charles Street. |

| Stanley Slack | 29 | Fireman; Auxiliary Fire Service, died on 12th December 1940 at Charles Street. |

| Tom Stacey | 31 | Fireman; Auxiliary Fire Service, died on 12th December 1940 at corner of Castle Street and Castle Green. |

| John William Swaby | 38 | Fireman; Auxiliary Fire Service, died on 12th December 1940 at Burgess Street. |

| Albert Wallace | 30 | Fireman Auxiliary Fire Service, died on 12 December 1940 at Marples Hotel, Fitzalan Square |

| Source: Imperial War Graves Commission |

| With regards to fire service fatalities: Albert Wallace an AFS Fireman. However, Albert's name does not appear on the Sheffield Fire Brigade 'Roll of Honour' and it is unclear whether he was on duty, or did not report for duty that night. He may have been assisting the injured, or he may have taken shelter from the bombing. This still remains a mystery, and the answer probably died with Albert but he still warrants being remembered. |

It is reported that the two most vivid impressions one had of Sheffield immediately after the sounding of the "All clear" were the numbers of people walking about, and the innumerable fires which completely enveloped great blocks in the centre of the city.

How so many people had escaped unharmed was a miracle. All had been hustled into shelters, and had either remained in one place during the nine hours of the raid or had to move from one shelter to another as more buildings caught fire and made shelters untenable.

Whilst it was perceived by most that the shelters were the safest place to be, this was not always the case and the following numbers of people lost their lives in them.

| Date | Shelter Location | No. Killed |

| 12/12/1940 | Craven Works, Darnall | 1 |

| 12/12/1940 | Fox Street, Pitsmoor | 5 |

| 12/12/1940 | Samuel Osborne, Clyde Works, The Wicker | 3 |

| 13/12/1940 | Earl Street, Town Centre | 1 |

| 13/12/1940 | Laurel Works, Nursery Street, The Wicker | 7 |

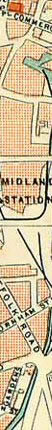

| 13/12/1940 | Porter Street (see map below), Town Centre | 12 |

| 13/12/1940 | St Mary's Road, Highfield | 1 |

|

| Early map showing location of Porter Street |

The heaviest loss of life in a single "incident" was at London Mart Hotel (locally known as Marple's) situated at the junction of High Street and Fitzalan Square. At the time of the direct hit it was estimated that between 60 and 70 persons—half of whom were women—were killed. However, with information taken from the records of the Imperial War Graves Commission the actual number can now be given as 49. >>View the Marple's List (Opens on a New Page) |

Early Photograph of Marple's Hotel |

At about 10.50 p.m. on the night of the bombing windows on the ground floor of Marple's were shattered when a bomb struck the premises of C. and A. Modes Ltd., on the opposite side of the street, . A number of people were cut by flying glass, and they went down into the cellar of the hotel, where soldiers, using field dressings, helped to bandage their wounds.

From the book - Sheffield at War - by Sheffield Star and Telegraph The ruins of Marple's. Opposite you can see the ruins of C&A Modes. |

At approximately 11.44 p.m. the hotel received a direct hit from a heavy calibre bomb, and the premises were completely destroyed. Before the hotel was hit, customers and staff alike had been calm throughout the evening. In fact, they had been singing popular choruses to the accompaniment of gun-fire and the dropping of bombs. The wrecked and smouldering ruins of the hotel were the subject of many stories for days after the raid. What follows is the official account of what happened, as pieced together by the police. Rescue work began at about 10 o'clock the morning of the 13th December. Within two or three hours seven men had been liberated. Two of the rescued walked away and their identity has never been revealed. |

The five other men rescued were: John Watson Kay, aged 46, Boma Road, Trentham, Stoke-on-Trent; Edward Riley, aged 36, Ecclesall Road, Sheffield; Ebenezer Tall, aged 42, Clarissa Street, Shoreditch; William Wallace King, Arbett Parade, Bristol; and Lionel George Ball, Knowle West, Bristol.

They told vivid stories of how they spent the night trapped in the cellars. How they could hardly breathe for smoke and dust . . . how they dug with their hands to make an air vent—how they dozed, weary and light-headed from the loss of blood.

It was calculated that over 1,000 tons of rubble were removed during the rescue operations, and the recovery operations continued on the site for several weeks.

|

| Bomb damage at Westbourne Road, Broomhill, from Sheffield Star and Telegraph archives |

The second mass raid lasted from 7.10 to 10.15 p.m. on Sunday, December 15th, and was confined to the East End of the city, extending from the south-east to the north-east.

As in the case of the first raid, it began with the dropping of a large number of incendiaries which caused many fires. Five parachute mines and about 100 H.E. bombs were dropped, which resulted in the deaths of a known 70 people.

|

The Air Raid Wardens who died during the raids:

|

| Date | Name | Age | Location |

| 12/12/40 | Charles Raynes | 35 | Bramall Lane |

| 12/12/40 | Constance Raynes | 36 | Bramall Lane |

| 12/12/40 | John Charles Butler | 33 | Cross Burgess Street |

| 12/12/40 | Harold Cooper DCM | 46 | Marples Hotel |

| 12/12/40 | John William Battersby | 53 | Stockton Street |

| 13/12/40 | John William Shaw | 29 | Sheaf Street |

| 13/12/40 | Harry Doyle | 56 | South View Road |

| 13/12/40 | Walter Shephard | 72 | Abbeydale Road |

| 15/12/40 | John Thomas Appleby | 60 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Joseph Armstrong | 44 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Leonora Armstrong | 41 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Frederick Brown | 38 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Robert Horace Cooper | 37 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Cecilia Gascoigne | 46 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | John Thomas Gascoigne | 50 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Lawrence Hall | 38 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Walter Hemmingfield | 54 | Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Victor George Thomas Salibury | 42 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 15/12/40 | Frank Donald Winter | 40 | ARP Post Coleford Road |

| 16/12/40 | George Edward Dickson | 53 | Manor Oaks Road |

A photograph taken a year on from the Blitz when an anniversary service was held on the site of the Warden's post in Coleford Road, where 10 people died |

| Other service people who gave their lives: |

| Date | Name | Age | Service | Location |

| 12/12/40 | Florence Elizabeth Wolstenholme | 30 | (FAP) First Aid Post | 25, Endwood Road |

| 12/12/40 | Joseph Morris | 58 | ARP Rescue Service | Marples Hotel |

| 12/12/40 | George Glaves | 45 | ARP Rescue Service | Westbrook Bank |

| 12/12/40 | Thomas Paramore | 35 | FAP (First Aid Post) | Westbrook Bank |

| 12/12/40 | Thomas Wilson | 52 | ARP Ambulance Driver | Westbrook Bank |

| 12/12/40 | Harry Wright | 59 | A.R.P. Rescue Service | Westbrook Bank |

| 13/12/40 | Frank Hides Monks | 52 | Constable Police War Reserve | Parkwood Road |

| 13/12/40 | George Beck | 34 | ARP Ambulance Driver | Shoreham Street |

| 13/12/40 | Percy Wood | 44 | Red Cross Ambulance Service | Shoreham Street |

| 13/12/40 | Lawrence Raymond Cross | 25 | (FAP) First Aid Post | St Mary's Road |

|

| Members of the ARP Ambulance Service on parade in 1940 From Sheffield Star and Telegraph archives |

As a result of these two raids 566 people were recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as having died , and the Sheffield Star reported that 1,817 people were injured. 2,849 houses were destroyed, 2,990 badly damaged and 71,785 slightly damaged. Eight schools were destroyed and 106 damaged. 1,218 business premises were destroyed and 2,255 were damaged. Eighteen churches including Valley Road Mission were destroyed and 90 damaged. 206 water mains were broken, 8 gasholders destroyed, 50 electric substations and 850 street lamps destroyed. 31 trams and 22 buses were wrecked.

Following the Sheffield Blitz further raids were mounted by the Luftwaffe. However, none of the matched the bombing intensity and loss of life that occurred on the 12-13th and 15th December 1940.

Extract - Sheffield City Council, Watch Committee, 19th December 1940 |

| Extract - Sheffield City Council, Watch Committee, 16th January 1941 Pursuant with the instruction given in Fire Brigade Circular 153/1940: 5 Sergeants and 20 Firemen of the regular Fire Brigade are allocated to the AFS as follows: To each of the 5 Divisional Stations (Elm Lane, Woodhouse Road, Norton Lane, Darnall Road and Division Street) 1 Sergeant . To each of the 20 Auxiliary Stations 1 Fireman. |

|

Date |

Area mainly affected |

Dead |

Seriously Injured |

Slightly Injured |

| 1941 | Jan. 9th | Dore | - | - | 1 |

| Jan. 16th | Aldine Court; Sheaf Street; Glossop Road | - | - | 3 | |

| Feb. 4th | Slayleigh Avenue | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| March 14th | Southey Hill area (land mines); Northumberland Road | 14 | 29 | 26 | |

| May 9th | Little London (Stokes' works); Hastings Road; Cemetery Road | 2 | 11 | 25 | |

| Totals | 17 |

41 |

59 |

For whatever reason the heavy industry in the East of Sheffield had been spared, and the production of war materials was able to proceed unhindered.

However, this intense period of inland bombing of industrial centres and London had shown that the Fire Brigades of Britain had difficulty in working together as their equipment and working practices were in many aspects different and incompatible. To rectify this a bill was rushed through Parliament to amalgamate all Britain's fire brigades into one body; the National Fire Service which came into being on the 18th August 1941.

This nationalisation was to end the running of the City's Fire Brigade by the Sheffield Police and thus ended the Sheffield Police Fire Brigade's 72 year service to the City.

| Sheffield Police Fire Brigade - The Final Roll Call |

| At the advent of the NFS the final roll call of the Sheffield Fire Brigade was 67 personnel. |

| Rank | Brigade No. | Name |

| Superintendent | Charles Teather | |

| Chief Inspector | John W Singleton | |

| Inspector | William D Outram | |

| Inspector | William H Gregory | |

| Sergeant | 33 | William S Humphries |

| Sergeant | 7 | William C Jeffery |

| Sergeant | 16 | John Genders |

| Sergeant | 26 | Albert Swift |

| Sergeant | 37 | Arnold Kay |

| Sergeant | 40 | Austin Shelley |

| Sergeant | 29 | Leslie Garside |

| Fireman | 12 | George Fred Belfield |

| Fireman | 15 | Joseph Weston |

| Fireman | 23 | Frederick Littlewood |

| Fireman | 17 | Arnold Jeffcock |

| Fireman | 6 | John W Grimstone |

| Fireman | 20 | Ernest Mathers |

| Fireman | 19 | Harry Marshall |

| Fireman | 9 | Frederick E Williams |

| Fireman | 10 | Walter Haslam |

| Fireman | 43 | Stanley Cooper |

| Fireman | 30 | William H Atkins |

| Fireman | 22 | Henry Carr |

| Fireman | 39 | Edward F Kemlo |

| Fireman | 13 | Eric Searston |

| Fireman | 44 | Charles Shirtcliffe |

| Fireman | 3 | Francis Hall |

| Fireman | 25 | Donald Roper |

| Fireman | 28 | Christopher Eyre |

| Fireman | 27 | Ivor W Blakey |

| Fireman | 45 | Sidney Harrison |

| Fireman | 46 | Lancelot W Hindhaugh |

| Fireman | 8 | Joseph G Digby |

| Fireman | 11 | John E Kilvington |

| Fireman | 41 | Archie Cornish |

| Fireman | 24 | Frank Taylor |

| Fireman | 14 | Leonard H Oldfield |

| Fireman | 1 | John Marshall |

| Fireman | 47 | Arthur P Whyte |

| Fireman | 48 | Hugh Whitney |

| Fireman | 49 | Alec Blakey |

| Fireman | 50 | Laurence Walker |

| Fireman | 18 | Frank F Smith |

| Fireman | 51 | Walter Taylor |

| Fireman | 36 | James C Brannan |

| Fireman | 52 | Aubrey B Booth |

| Fireman | 32 | Frederick W Belfield |

| Fireman | 35 | Joseph H Currier |

| Fireman | 38 | Douglas W Lightning |

| Fireman | 42 | Austin Southworth |

| Fireman | 53 | Albert A Swift |

| Fireman | 54 | William A Unwin |

| Fireman | 56 | Cyril F Woodward |

| Fireman | 21 | George H Whitfield |

| Fireman | 55 | Frank D Styan |

| Fireman | 57 | Cecil G Littlewood |

| Fireman | 5 | Robert F Hood |

| Fireman | 58 | Harold Lake |

| Fireman | 31 | Joshua A Arnold* |

| Fireman | 59 | Joseph Tingle |

| Fireman | 60 | David D Lennie |

| Fireman | 61 | Robert Marshall |

| Fireman | 62 | James F Fairclough |

| Fireman | 63 | Robert L Maskrey |

| Fireman | 64 | Reginald R Bradley |

| Fireman | 65 | Clifford J Hemstalk |

| Fireman | 4 | Sidney B Jowett |

| The above list has been compiled from information supplied by the late Ronald Weston |

* Fm 31 Joshua A Arnold

Joss joined the fire division of Sheffield City Police in 1938 but was called up for war service in 1940. He joined the RAF Police and was a motorcycle policeman, escorting aircraft bodies. After the war he re-joined the Fire Service, and he and his family lived at Rockingham Street (flat 35) and later at Norton Fire Station (House No 1). After many years of service he was seconded to the Home Office Civil Defence Training Centre at Moreton-in-Marsh (later the Fire Service College), where he taught convoy control to Civil Defence volunteers becoming probably the only motorcycle instructor Sheffield Fire Brigade has ever had. Information provided by Joss' son David Arnold, a retired policeman.

| >>View a full version of the Nominal Roll for 1941 with extra information provided by the late Ronald Weston >> View the original rescued pages for 1941 |

| >>The Sheffield Roll of Honour (A full list of people who lost their lives in the bombings of Sheffield). | |

| >>The Sheffield Bombing Map (An original copy of the map showing where the bombs fell during the 'Sheffield Blitz'). |

Editors Notes:

In Christopher Eyre's story, he states that he was informed that a pump stationed on *Porter Street had been blown to bits, and two men killed. According to official records this could be incorrect. It appears that the pump that received the direct hit was stationed on Burgess Street.

* Porter Street: Now no longer in existence. At the time it ran from Matilda Street to the end of Bramall Lane.

What was not made public, was that the Germans flew by a beam, an early kind of Radar. This was fixed on a point and then the German bombers flew down the beam to their target. The interception of enemy radio beams indicated that Sheffield was the objective. The authorities were warned, anti aircraft gun batteries, police and all branches of the Civil Defence services were ready. However, the intelligence services had found a way to bend this beam and instead of the point the Germans had chosen, which was the Duke of Wellington pub on Carlisle Street, the beam had been bent so that the Germans flew straight to the city centre instead. This saved the steel works but threw the city centre into chaos and killed many people. However, this is just a theory, and is countered by other opinions which state that the bombing of the city centre was a deliberate terror raid.

Because of the nature of the city's industries the people of Sheffield expected that bombing from the air would be an early and sustained war experience, though none dared to prophesy its nature, extent or toll; all that could be done was to prepare.

Why did the bombing stop?

German historians usually place the beginning of the Battle of Britain in mid-August 1940 and end it in May 1941, on the withdrawal of the bomber units in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the Campaign against the USSR on 22 June 1941.

Why divert bombers from their objective to the centre of Sheffield?

For those readers who only remember Sheffield from the early 1970's onwards, and especially the East End as being a place of sports stadia and entertainment complexes. The East End had a completely different character up until the end of 1960.

The Sheffield East End of the 1940's:

English Steel Corporation - Vickers Works: For the first 18 months it housed the only drop hammer capable of forging crankshafts for Spitfires and other important aircraft. It also produced armour, springs etc for a range of tanks - Churchill's, Cromwell's, Valentines, Sherman's and Centaurs were supplied by the English Steel Corporation. The fire power of the British ships came from their cannons, and 40% of the forgings for them came from English Steel. The castings for many of the British Bombs also emanated from the works.

United Steel: Nearly 3,000,000 tons of semi-finished steel was produced at this works during the war. Of this half was re-rolled into the firms continuous bar and strip mills. The bar mill produced 270,000 tons of shell steel bars, as well as large tonnages of rivet, bolt and nut bars and ferro concrete bars. Gun forgings were also produced for 2 pounder, 25 pounder and the 4.5 inch and 3.7 inch anti-aircraft guns.

Edgar Allen & Co: Made 10,000 tons of armour plate. Sheets for for more than 1,115,600 helmets for British troops in austenitic 11-14 per cent manganese steel were supplied to the helmet makers. They also made enough bullet core steel to produce 512,750 cartridges. The track work department drilled and tapped 7,312 tank plates, and ground 837,600 aircraft parts.

Arthur Balfour and Co. Ltd: Specialised in the production of high speed tool steels. This metal was extensively used for the machining shells and the production of reamers which could be used in continuous work.

Firth Vickers Stainless Steels: This company produced vast amounts of stainless steel for aircraft production. The company also produced welding wire for the production of tanks, at a rate of 70 tons per month.

Brown Bailey Mills: Makers of special and alloy steel. 7,000 blocks of special steel were produced and ultimately made, by another company, into torpedo air vessels, mainly for the Fleet Air Arm; upwards of 9,000 guns barrels were produced, and the number of rifle barrels, either in the form of forgings, or merely as round bars, was well over a million.

Hatfields Ltd: Produced 4,550,000 Shells and bombs. They also produced 42,000 tons of bullet proof and armour plate for the Royal Navy, Army and Royal Air Force, and were one of the major contributors of armour protection, both for tanks and for aircraft. In Remembrance of my Grandmother, Ellen Jane Plane, who worked as a crane driver at Hatfields throughout the Second World War.

Whilst I have named only a few of the major companies involved, and I apologise to the other 100 or so not named. I think the above list gives the reader some idea of why someone might want to bend a radio beam and send the Luftwaffe over the city centre instead.

The Luftwaffe's main intention was to destroy the factories along the Don Valley, and according to the official reports the first wave of bombers (Heinkels carrying incendiary weapons) encountered low cloud in the target area. However, this was contradicted by a report in the Sheffield Star which stated that: "Conditions for bombing were perfect. There was a full moon in a cloudless sky and a keen frost had whitened the roofs". It was also speculated that a Luftwaffe navigator mistook the Moor for Attercliffe Road. (the major arterial road through the industrial belt). Nevertheless, once the first wave of bombers had marked the target area with incendiaries, the second wave of planes carrying high explosives arrived at 9pm and bombed the fires in the heart of the city thinking these marked their target.

It will probably never be known what the exact objective was of the first and more disastrous of the two raids. In their official communique the Germans claimed to have hit their targets of steel and war works, but, either by accident or design, this is the one thing they did not do. The attack was one on civilians and non-military objects.

The second raid on the 15th December was actually confined to the East End, but little damage was done to factories undertaking war production.

Both raids, therefore, were a failure from a military point of view. The civilian population, though shocked and temporarily dazed, did not lose heart, nerve, or confidence. If the object of the raids was to break their spirit they failed; it left the people of Sheffield embittered and a more determined people.